SEWA was born as a trade union of poor self-employed women in 1972, in the city of Ahmedabad, Gujarat. It grew out of the Women’s Wing of the Textile Labour association, TLA, India’s oldest and largest union of textile workers founded in 1920 by Anasuya Sarabhai and Mahatma Gandhi. The original purpose of the Women’s Wing was to provide training in sewing, spinning, knitting, embroidery, and other welfare activities to the wives and daughters of mill workers.

In 1971, a small group of migrant women working as handcart-pullers / headloaders in Ahmedabad’s cloth market came to the TLA looking for help in securing decent wages. The women lived on the streets, and were too poor to afford even a shack. They all worked in the city’s thriving cloth market, ferrying bolts of cloth between wholesalers and retailers. Wholesale shop-owners would pay them per job, at exploitative wages. Even more exploited than the handcart-pullers were the head-loaders, who ferried huge loads on their heads for a pittance. Ela Bhatt sat in the market with the agitated women as they recounted their struggles with ruthless contractors, erratic jobs, and low wages.

Following the meeting, Ela Bhatt wrote an article in the local newspaper recounting the unfair wages, and other problems of the head-loaders.

The cloth merchants countered the charges against them with an article of their own, announcing the fair wages they were paying the head-loaders. Of course, the women did not receive they fair wages they claimed, so the Women’s Wing reprinted the merchant’s claims on little cards and distributed them throughout the market to use as leverage against the merchants.

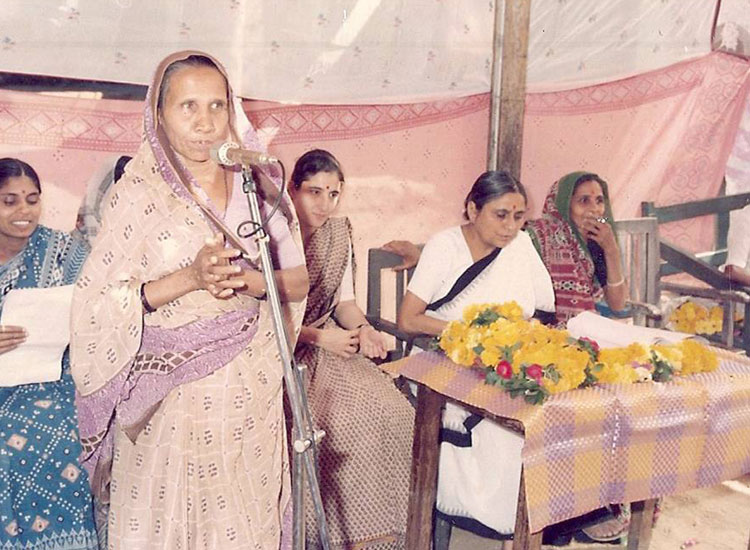

This strategy was so effective that word spread among the women, and a group of used-clothes dealers approached the Women’s Wing with their own grievances. A public meeting of used-garment dealers was called and over hundred women attended. During the meeting in a public park, the women suggested that they form an association of their own. Thus, following an appeal from the women, and at the initiative of Ela Bhatt, and the president of the TLA, Arvind Buch, the idea of forming Self-Employed Women’s Association (SEWA) – an association of poor self-employed women workers from the informal economy was conceptualized in December 1971.

The women felt that as a workers’ association, SEWA should establish itself as a trade union. This was a fairly novel idea, because the self-employed have no history of organizing. So SEWA’s first struggle was registering as a trade union.

The State Labour Department refused to register SEWA as a union because in their view, if there was no employer involved, who were the workers organizing against? SEWA argued that the purpose of a union was to unify the workers; it did not need an employer to justify its existence. SEWA’s argument prevailed, and it was finally registered as a trade union on April 12, 1972 – A day we celebrate in SEWA as “Self-Employed day”.

Since 1972, SEWA membership has grown at a steady pace, drawing self-employed women from many different trades into the union: from vegetable vendors to incense-stick rollers, from junksmiths to waste-recyclers. The Women’s Decade, beginning in 1975 also gave a boost to the growth of SEWA, placing it firmly within the women’s movement. In 1977, SEWA’s General Secretary, Ela Bhatt, was awarded the prestigious Ramon Magsaysay Award and this brought international recognition to SEWA.

By 1981, relations between SEWA and TLA had become strained. The interests of TLA, representing workers in the organized sector did not align easily with the interests of SEWA, representing unorganized women workers.

Furthermore, the textile mills of Ahmedabad were closing down at a steady pace, and the textile industry was changing rapidly, leaving the union to cope with thousands of unemployed workers with no hope of getting their jobs back. SEWA on the other hand was charting new territory at every step, establishing a cooperative bank for its illiterate members, and questioning the definition of worker under the current labour law. Eventually, TLA pushed SEWA out from its fold, and withdrew all support. Although sorry to leave the historic Gandhian parent institution, SEWA was ready to face any challenges that came its way.

The women of SEWA realized that they were now free to forge a new path, form new relationships, and innovate solutions that fit their needs. With all the creativity and courage at their command, the women have built SEWA into a democratic, inclusive, responsive, dynamic, and self-sustaining organization.

SEWA has found that when women take the lead, their approach is collaborative, and their solutions are often unconventional. The joint action of union and trade cooperatives has led to a holistic approach that is characteristic of SEWA.

Along the way, our landmarks have included the SEWA Bank, started in 1974, which gave birth to the microfinance movement across the world. In 1996, the ILO recognized home-based workers as workers, thereby protecting them with basic labour standards. And in 2014, India passed the Street Vendor’s Act to recognize the concept of Natural Markets in cities, and the rights of vendors to earn their livelihoods in them. These significant victories, were the result of a long and tenacious struggle by SEWA, bringing visibility, voice, and validity to the work of the unorganized sector workers of the country.

Over the years, several SEWAs have grown organically across India, bringing together poor, self-employed women working in over 125 different trades, and belonging to many different castes and religions. Their struggles and challenges are equally wide, ranging from fair wages, healthcare, insurance, banking, housing, to skill upgradation, market access, and training. These issues are not confined to the self-employed in India alone. Self-employed women in South Asia, in South Africa, and countries in Latin America, have also started SEWAs to meet local challenges.

SEWA has grown from an organization to a movement. This movement is at the confluence of the labour movement, the cooperative movement, and the women’s movement.